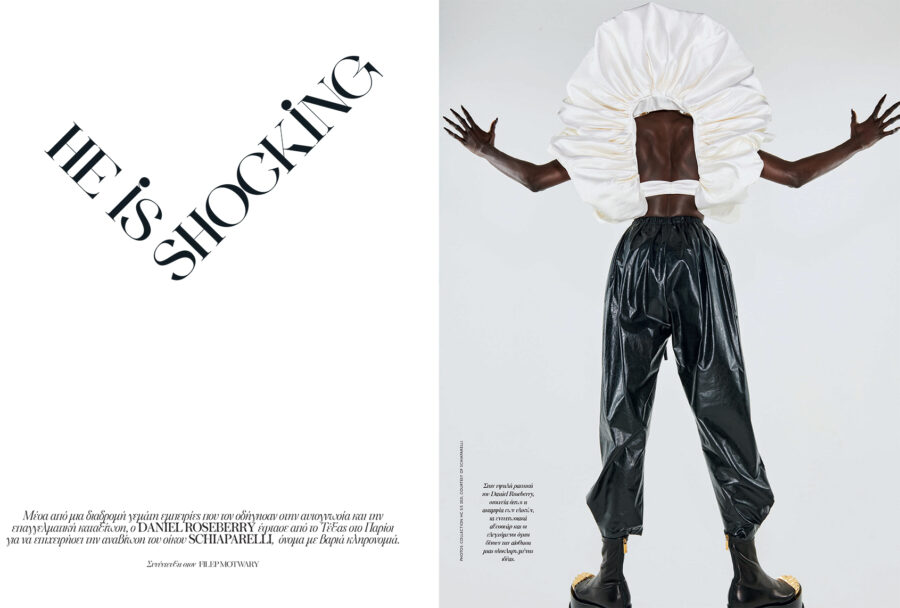

DANIEL ROSEBERRY | 2021

Interview Filep Motwary

Through a journey rich in emotion, intuition, and radical self-discovery, Daniel Roseberry has carved a path that places him firmly among fashion’s most defining voices of the modern era. From the sun-bleached plains of Texas to the storied avenues of Paris, the young designer undertook the audacious task of reawakening the legendary House of Schiaparelli — a maison heavy with historical gravity and surrealist legacy.

Within less than two years of arriving at Schiaparelli, Roseberry had already stamped his signature on the fashion world. In January 2021, his name became entwined with a global moment that felt both cinematic and deeply real: the inauguration of the 46th U.S. President, Joe Biden. Draped in a striking Schiaparelli ensemble, Lady Gaga delivered the national anthem, a golden dove of peace gleaming at her chest — pinned close to the heart. It was a fashion moment that didn’t just grace headlines; it rewrote them in real time.

“I’m moved that you ask about that day,” Roseberry confides. “The world’s response was immediate, intense, and heartfelt. Among the messages of love and solidarity, I felt the need to pause — to understand the weight of that moment. What it meant to me, to my journey, to my family, to my country. It was deeply personal, yet profoundly collective. It felt like a threshold — and we were ready to cross it.”

The gown, Gaga’s now-iconic look, was created in just eight days. The crimson fabric was dyed in Paris; the sculpted top, crafted from fine cashmere, was added later. “It all came together on instinct and faith in my team,” he says. “I’m deeply grateful for the technical brilliance and passion of the atelier — they are the invisible force behind every creation. That energy — impulsive, yet full of trust — is what I want to preserve for as long as I walk this path. There’s no room for cynicism in my work, or in who I am.”

Every Schiaparelli collection under the 33-year-old designer is a call to reimagine gender, identity, and form through a lens that is fluid, fearless, and wholly liberated. “I’m queer, I’m gay, and some mornings I wake up wondering — do I feel more masculine or more feminine today? Not as a role, but as a feeling. That fluidity is where my creativity begins. It’s how I connect with the world.”

Raised in Plano, Texas — far from the fashion capitals — Roseberry’s childhood was steeped in faith and tradition. He’s the son and brother of preachers. “Every Sunday, I’d hear my father preaching in a large Episcopal church. He was a magnetic speaker. But I was caught at a crossroads — between the formality of religious life and my mother’s artistic soul. She was a calligrapher from a lineage of painters.”

Their home, as he describes, was filled with art, symbols, and quiet tensions — a space where beauty, belief, and personal longing collided. “Every summer, I’d travel to New York to visit my grandmother on Long Island. Her home was a temple of beauty. My parents never had money — I often felt a sense of lack. But my father’s faith opened doors. I got a scholarship to an elite private school. That was privilege — and the seed of everything that followed.”

Today, Roseberry is the only American couturier at the helm of a major Parisian house. “I still feel like an outsider moving on instinct — almost like Elsa’s spirit is guiding me. She, too, was always the rebel, always the stranger.” A recent image that deeply touched him? A woman who recreated Gaga’s inauguration look entirely in crochet. “They asked me if I ever imagined that. And I said — yes. Because fashion belongs to everyone. And it can be born in the most unexpected corners of the world.”

It was this singular opportunity that truly shaped him. Spending time in the aristocratic enclaves of Dallas among his privileged classmates exposed him to a world of new interests, perspectives, and possibilities. He recalls a moment of awakening: a Style Channel documentary on Michael Kors.

“Watching Kors’s journey—seeing the backstage frenzy, the allure, the sheer theatre of fashion—for the first time, I felt something click. I could finally picture myself, however abstractly, within that world. That’s when I started sketching. And not long after, I made the life-changing decision to move to New York. I remember being terrified—torn between two worlds: my sexuality and my religious upbringing.”

But liberation didn’t come easily.

I remember seeing him backstage at Thom Browne, where his career began and where he remained for a decade—always focused, almost austere. I didn’t know much about him then, only that he was integral to the team. That impression solidified over time, as I’d spot him at every show, meticulously adjusting garments just moments before they hit the runway, in direct dialogue with Browne himself. His posture exuded discipline; his gaze, a quiet intensity tinged with porcelain-like sensitivity.

He says his long-awaited release came in 2019, with his first collection for Schiaparelli.

“Since I was eight years old, I wore uniforms—at church, at school, and later in adulthood at Thom Browne, where we all wore that signature flannel suit. When I left, I suddenly plunged into an abyss of uncertainty. I had no idea who I was sartorially on a day-to-day level. I had no idea where to go as a designer either. It was an intensely personal journey—and that evolution is visible in every collection I’ve done since. I’ll never forget what Tim Blanks said about my debut: ‘It wasn’t perfect, but it was brave.’ That—the essence of bravery—is what guides me still.”

We talk about the seismic shifts fashion has experienced over the last decade. The death of Alexander McQueen and the dramatic fall of John Galliano from Dior—one literal, the other symbolic—he agrees, were a double gut-punch. “With them,” he says, “we lost grandeur. We lost the dream of dressing up. That hunger for excess and spectacle? It drowned with them.”

I ask him what ran through his mind when he was offered the creative helm at Schiaparelli.

“It was December. I was in my Chinatown studio in Manhattan. That became the central theme of my first collection—a conceptual mise-en-scène, imagining what this house could look like if it lived in our era. I think that’s what the brand was truly searching for: someone who could understand the spirit of Schiaparelli without being shackled to her codes or obsessing over the archives. But of course, the reality I found when I arrived was something else entirely.”

Under Daniel Roseberry, Schiaparelli has re-emerged with uncanny clarity. His emphasis on intricate embellishment and otherworldly accessories has brought the house closer than ever to Elsa’s original spirit—nearly 100 years later. In an era where surrealism feels more relevant than ever—locked indoors, staring into screen after screen, drained by monotony—Roseberry reminds us of fashion’s transcendent power.

“More than anything,” he says, “I needed the freedom to discover the house’s language for myself. The previous leadership was too fixated on visual callbacks and archival mimicry. That might thrill some, but I honestly don’t think Elsa would’ve wanted me to design for people who get excited over embroidered faces on cocktail dresses.

Diego Della Valle, the house’s owner, always says: Schiaparelli is fashion’s final dream. And I came here to keep that dream alive.”

“We are the jewel of a billion-dollar industry,” he continues. “And now, more than ever, we must protect its values while pushing forward. What happened with Lady Gaga—that moment—was exactly what we needed. Now, the world knows our name. People who never would’ve spoken of Schiaparelli before are finally talking about us.”

Elsa Schiaparelli was particularly known for her collaborations with the Surrealists of the 1930s — Salvador Dalí, Jean Cocteau, Man Ray. What most people don’t know is her remarkable ability to create sensual eveningwear: garments that closely followed the body’s form, inspired by the artworks of the movement. The human skeleton, decaying flesh, shellfish, the third eye — these were some of the themes that inspired her. Fuchsia (shocking pink) was her favorite color, and she had a fondness for accessories like hats and gloves, as well as for unexpected and oversized jewelry. Influenced by the cultural trend of the time — which often placed hands at the center of films, photographs, and collages, like those by Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore — hands were glorified in Schiaparelli’s work. Eyes, noses, lips, and fingers were recurring obsessions both for Dalí and the Italian designer, and throughout their long collaboration, they experimented with creating imaginative adornments for the entire body.

I ask Daniel Roseberry about his impressions upon finally visiting the house’s rich, beyond-imagination archive for the first time. “What I noticed,” he says, “is that the clothes seemed to take shape gradually — something I attribute to the seams, which feel somewhat spontaneous, and often there’s ambiguity and asymmetry in the methods used to finish them. This places the designer in a different realm from her contemporaries — one where intuition takes precedence over precision in how the garments were assembled and sewn. That’s how I felt a kind of familiarity with Elsa and her work. She had a strange obsession with the tension of colors, which often led to something almost sarcastic. She was a genius.”

Is surrealism ultimately a concept that echoes through time? Does it evolve, or is it static? And what is its relevance today?

“I believe that the concept of the body is an unchanging value, and the idea of its displacement — something that truly stems from surrealism — is completely relevant to the times we’re living in. I’m not trying to recover a visual language from the past that eventually reached a dead end. Surrealism is a state that gives us the right to redefine. I think that people constantly learn through their bodies — I think of Egyptian mummification, the Renaissance, the 1950s — by observing how the body reflects the intentions behind any aesthetic intervention. When we place the body in a ritual context, we move toward immortality. On a personal level, until I was 20, I was in constant conflict with my body. I smoked for ten years and generally lived in a state of exhaustion. That was a very dark period. At Thom Browne, I was a workaholic, which left no room for me to think positively about my life. Suddenly, when I turned 30, something happened that made me love myself and find peace with what used to bother me. My body became my friend and companion, rather than something that repulsed me. This new condition aligned with my professional perspective on the body overall, and for the first time, the creative exploration of it became a source of great joy,” he emphasizes.

The conversation shifts to his current Haute Couture collection and the striking accessories that accompany it. Extremely photogenic, it’s designed for irresistible women like Kamala Harris, the new Vice President of the United States and a symbol of female heroism. This time, Roseberry’s instinct led him to a frenzy of ideas taken to their extreme, revealing his immense talent and leading the world of Schiaparelli to new horizons. Everything we’d seen from him until now was just the warm-up.

“I knew this collection would be presented online, and that changed my mindset — it was freeing in a way. I don’t want to provocatively say that the collection looks better in person, because I believe if someone has seen the photos and video, they can form an opinion. I really wanted it to succeed digitally, and I tried to create something very graphic — using textures and colors like pink, white, and black. There were references to the body and its training, as well as intricate embroidery to keep the intensity high. Elements like rigidity in certain materials, and jewelry designed for less complex but voluminous silhouettes, gave a sense of a complete vision. I agree with you that it’s a very photogenic moment for the house of Schiaparelli and that, from a design perspective, the collection is exactly where it should be,” he says with a laugh.

What’s the most important quality a fashion designer should have? I ask.

“The most important thing is asking for help when you need it. When I don’t know something, I can’t pretend otherwise — especially when there are people around me who do know. I have friends who find that kind of admission unthinkable, but it causes problems for them. I wouldn’t be where I am today if I didn’t ask questions or give myself the chance to learn from others.”

Finally, he draws a comparison between Haute Couture and prêt-à-porter, explaining that the latter allows for changes and self-improvement right up to the final moment before a show.

“With Couture, it’s exactly the opposite. I had to fight for two seasons with the timelines and the fact that I couldn’t make changes. At the same time, my designs had to radiate confidence — just like I did — so I could deliver them to the atelier, trusting that they would bring them to life. When I first arrived here, I realized that my role as creative director ends at the atelier’s doorstep. That aligns me with the tradition of Haute Couture and the legacy of the Schiaparelli house. I can’t claim ownership of the rules just yet, and it’s no secret that I’m just an American in Paris without the experience of a Couturier… But I’m learning every day. I’m trying.”

This is the opening spread from Schiaparelli’s creative director’s interview of Daniel Roseberry by Filep Motwary, as it was published in Vogue Greece, issue May 2021.

The interview was published in Vogue Greece, in May 2021.

Texas-born Daniel Roseberry took over as artistic director at Schiaparelli following Bertrand Guyon’s departure in April 2019, having previously spent 11 years at ready-to-wear brand Thom Browne . His debut collection had “an audacity that had a perfect, refreshing logic,” said BoF Editor-at-Large Tim Blanks in his review.

Roseberry studied at Fashion Institute of Technology in New York before starting his career at Thom Browne in 2008. Over the last five years, Roseberry acted as the brand’s design director of men’s and women’s collections.

In April 2019, Schiaparelli announced the departure of Bertrand Guyon, who held the role of design director for four years. A week later, Daniel Roseberry was announced as Guyon’s successor, to take charge of all collections and projects at the storied Place Vendôme house. The designer debuted his first collection for the house for the Autumn/Winter 2019 couture season, despite never working in a couture atelier before. Notably, he also does not speak French but instead, another member of the atelier translates his instructions.

Photo by Estelle Hanania. Styled by Patti Wilson for The New York Times