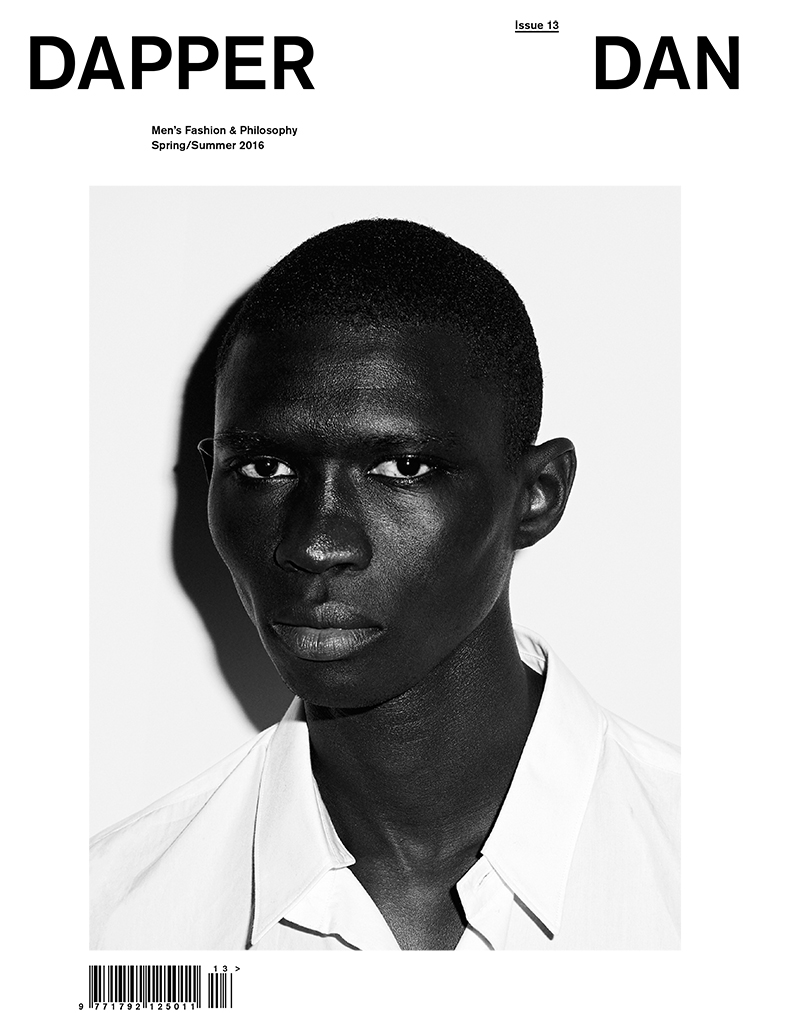

INTERVIEW in DAPPER DAN #13

Interview by Kim Laidlaw with Filep Motwary about his curatorial project, “Haute-à-Porter” a new exhibit that opened in Belgium’s Hasselt Modemuseum. The interview was published in Dapper Dan Magazine issue #13, released in April 2016.

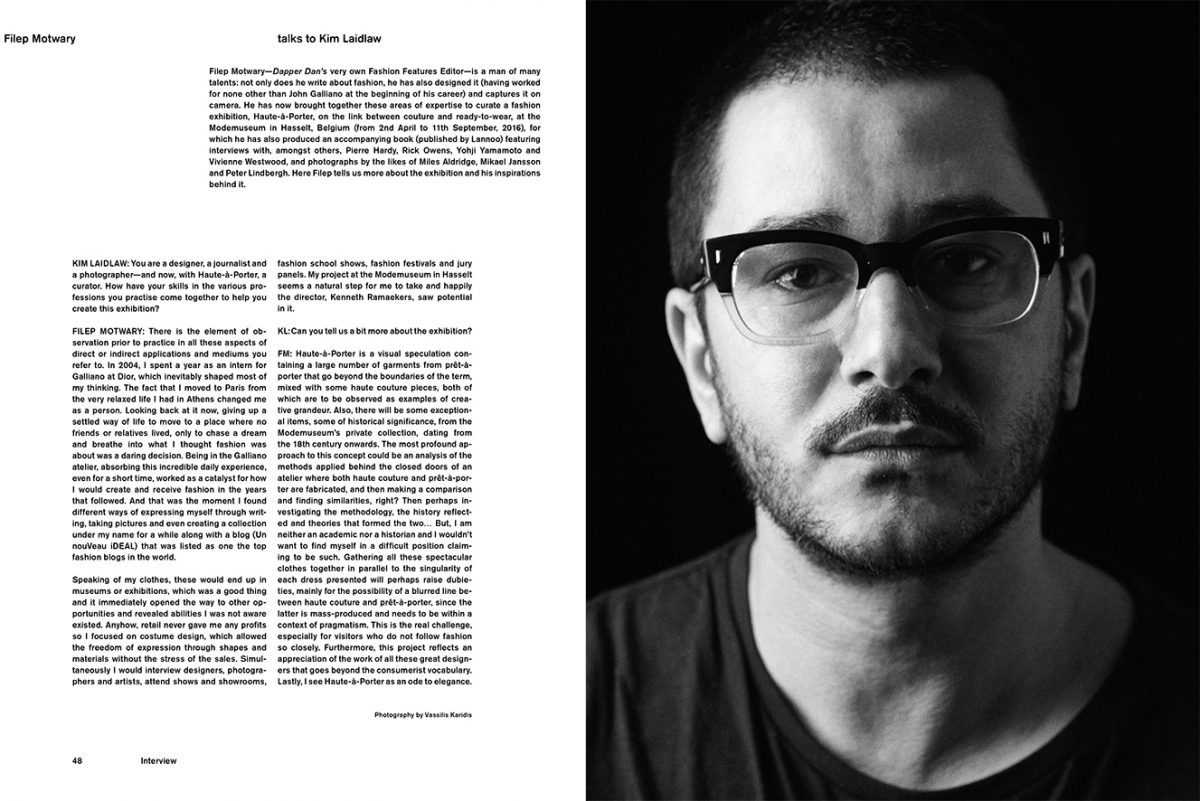

“Filep Motwary—Dapper Dan’s very own Fashion Features Editor—is a man of many talents: not only does he write about fashion, he has also designed it (having worked for none other than John Galliano at the beginning of his career) and captures it on camera. He has now brought together these areas of expertise to curate a fashion exhibition, Haute-à-Porter, on the link between couture and ready-to-wear, at the Modemuseum in Hasselt, Belgium (from 2nd April to 11th September, 2016), for which he has also produced an accompanying book (published by Lannoo) featuring interviews with, amongst others, Pierre Hardy, Rick Owens, Yohji Yamamoto and Vivienne Westwood, and photographs by the likes of Miles Aldridge, Mikael Jansson and Peter Lindbergh. Here Filep tells us more about the exhibition and his inspirations behind it.”

KIM LAIDLAW: You are a designer, a journalist and a photographer—and now, with Haute-à-Porter, a curator. How have your skills in the various professions you practise come together to help you create this exhibition?

FILEP MOTWARY: There is the element of observation prior to practice in all these aspects of direct or indirect applications and mediums you refer to. In 2004, I spent a year as an intern for Galliano at Dior, which inevitably shaped most of my thinking. The fact that I moved to Paris from the very relaxed life I had in Athens changed me as a person. Looking back at it now, giving up a settled way of life to move to a place where no friends or relatives lived, only to chase a dream and breathe into what I thought fashion was about was a daring decision. Being in the Galliano atelier, absorbing this incredible daily experience, even for a short time, worked as a catalyst for how I would create and receive fashion in the years that followed.

And that was the moment I found different ways of expressing myself through writing, taking pictures and even creating a collection under my name for a while along with a blog (Un nouVeau iDEAL) that was listed as one the top fashion blogs in the world. Speaking of my clothes, these would end up in museums or exhibitions, which was a good thing and it immediately opened the way to other opportunities and revealed abilities I was not aware existed. Anyhow, retail never gave me any profits so I focused on costume design, which allowed the freedom of expression through shapes and materials without the stress of the sales. Simultaneously I would interview designers, photographers and artists, attend shows and showrooms, fashion school shows, fashion festivals and jury panels.

My project at the Modemuseum in Hasselt seems a natural step for me to take and happily the director, Kenneth Ramaekers, saw potential in it.

KL: Can you tell us a bit more about the exhibition?

FM: Haute-à-Porter is a visual speculation containing a large number of garments from prêt-àporter that go beyond the boundaries of the term, mixed with some haute couture pieces, both of which are to be observed as examples of creative grandeur.

Also, there will be some exceptional items, some of historical significance, from the Modemuseum’s private collection, dating from the 18th century onwards. The most profound approach to this concept could be an analysis of the methods applied behind the closed doors of an atelier where both haute couture and prêt-à-porter are fabricated, and then making a comparison and finding similarities, right? Then perhaps investigating the methodology, the history reflected and theories that formed the two… But, I am neither an academic nor a historian and I wouldn’t want to find myself in a difficult position claiming to be such. Gathering all these spectacular clothes together in parallel to the singularity of each dress presented will perhaps raise dubieties, mainly for the possibility of a blurred line between haute couture and prêt-à-porter, since the latter is mass-produced and needs to be within a context of pragmatism. This is the real challenge, especially for visitors who do not follow fashion so closely. Furthermore, this project reflects an appreciation of the work of all these great designers that goes beyond the consumerist vocabulary. Lastly, I see Haute-à-Porter as an ode to elegance.

KL: What is your favourite piece on display in the exhibition and why?

FM: Each garment has its own calibre, its own vocabulary and the story within which it was created, as well as the designer’s creative language. Separated in to themes such as embellishment, draping, the corset, print and crinoline, I feel that the clothes will speak for themselves. Furthermore, the exhibition is about pieces I favour—a taste from collections that caused a stir and emotion in the past 20 to 25 years. Each garment was chosen for its own existence.

KL: The exhibition examines haute couture’s relationship with prêt-à-porter. How has the former influenced the latter?

FM: It is a fact that couture requires a certain degree of skills, and is created in the atelier with a focus on details, artisanship and so on. Pretà- porter is supposed to be much easier in the making and to be worn “on the streets”. But then you have someone like Rei Kawakubo, for example, who breaks any commercial rules by being herself—a complete outsider who turns fashion upside down.

Take, for instance, her spring 2016 show and compare it to Dior’s spring/summer 2003 couture collection by John Galliano. Or, for example, Josep Font’s work for Delpozo, which is very recent, yet reflects elements of classic haute couture.

Or Yohji Yamamoto’s impeccable ability to create emotion every time a girl walks out onto the catwalk and also the elements he always likes to include, like volume, corsetry, crinoline and the suit. Every time I watch his wedding collection (spring ‘99) on Youtube, I feel vulnerable. Or Vivienne Westwood’s approach to the present through history and how she recreates the silhouette, always with a twist of pattern—which is so hard to copy once the pieces are sewn together. It is unquestionable that the work of certain prêta- porter designers is far from being prêt-à-porter.

KL: Haute couture pieces are often spectacular and theatrical but not actually wearable in real life. Is haute couture the place where fashion and art collide? We are seeing more and more fashion exhibitions—including this one—and a more important, academic appreciation of fashion history. Is this the true role of haute couture: fashion as art and cultural heritage?

FM: To me, an haute couture presentation is a demonstration of the designer’s abilities as an orchestra conductor. The models resemble the melody and the garments are the instruments through the craftsmanship and the artisanship applied by the skilful hands of the atelier. It is supposed to attract exactly like a male peacock’s tail in full display. Couture has the freedom to be creative no matter the cost, leading to enormous possibilities in the way sketches and ideas are translated into a reality that fails to become monotonous. Rightfully, some of these garments are considered as art. They should be seen as art and must be presented within the deserved context for the entire world to see.

KL: That said, the flip side is that some would argue that haute couture is out-dated and frivolous. What would you say to that?

FM: There is a very austere editing, sometimes even dry, by journalists to what the world sees online after each fashion week, so I would say the term “out-dated” is not at all the case. Frivolous, yes and this is essential as long as it adds to the values of creativity and preserves the purpose of the term “fashion” and enforces the reason to be embraced for its spirit.

KL: What do you think about high-street fast fashion—the quick, cheap, disposable kind that often replicates the pieces seen on catwalks? How does haute couture fit in with this? How is this rapid consumption of fashion changing the roles of haute couture and prêt-à-porter today? Is haute couture anachronistic in a world with such a fast turnaround?

FM: Take for instance Balmain’s recent collaboration with H&M, which was an overnight sell-out. To me, what Olivier Rousteing does for Balmain is haute couture and the prices some of these pieces sell at confirm that there’s a specialty in their making. His skills in draping, embellishment and craft are undeniable. And yet, one cannot help but wonder how the actual clients of such a high-end brand feel when they see their most cherished jacket sold at a very low price.

I don’t think haute couture is anachronistic. Couture should remain what it is with perhaps a bit of anarchy here and there. But always a hands-on process, otherwise what’s the point? It’s pleasant to see designers believing in it—like Giambattista Valli and Alexis Mabille for example, who are both pioneering in couture. Or Chanel, a House that never fails to be luxurious even when using the latest in technology or ecology, like in the spring/ summer 2016 couture show. For as long as there are people buying it, for any reason right or wrong, haute couture must stay “haute” and for the few.

KL: How do you think social media and the Internet— what with street style, the likes of fashion bloggers, and the ubiquitous selfies—are influencing the way we consume fashion today?

FM: We know that certain bloggers became an inspiration and in some cases ambassadors of a brand or a magazine through their personal style and writing. I salute it as their personal achievement. In my book “Haute-a-Porter”, which will be released simultaneously with the exhibition, there is an interview I did with Valerie Steele, director and chief curator at FIT New York, where she explains this phenomenon and how fashion’s interaction with social media shaped this new era we live in.

KL: Would you rather have one piece of exquisite haute couture or a significantly larger haul of prêtà- porter pieces? FM: Both! KL: The crafts associated with haute couture are very specialised, with artisans for each step of the way being experts in their field, whether it be beading or lace or leatherwork. Chanel has bought many of these artisan companies in order to preserve the craftsmanship they use for their couture pieces. Is there a worry that these traditions— that such an important part of fashion history and heritage—might die out?

FM: How could couture maintain its values if they are not preserved, if there is no interaction between the designer, the craftsmen and clients for whom these garments are made based on their individual measurements? Haute couture is a Parisian speciality; it was named so in France. The French have an intense flair for envisioning fashion and applying it in the most exquisite ways. There are so many examples of non-French designers whose work made sense in their home countries but it was imperfect and not so refined, in many cases aggressive even, until they moved to the City of Light to work with the French. Heritage needs to be preserved and to be passed on to future generations. It’s a matter of identity and principles. Otherwise a new word must be invented to describe a type of haute couture that is no longer relevant to what the original term once meant.